[Series] Going to Mars Pt. 2

It probably comes as no surprise that to undertake a mission to land a manned mission to Mars comes as an enormous challenge requiring the best and brightest that humanity has to offer. Mars is far away, really far away. To put things in perspective, the Moon orbits the Earth at about

384,400 km; a staggering figure, but demonstrably surmountable as evidenced by the twelve men who have stepped foot on its surface since 1969. With that in mind, Mars offers a substantially more difficult target to hit.

Mars bears an eccentric orbit around the sun, the most lopsided orbit out of the planets in our solar system.

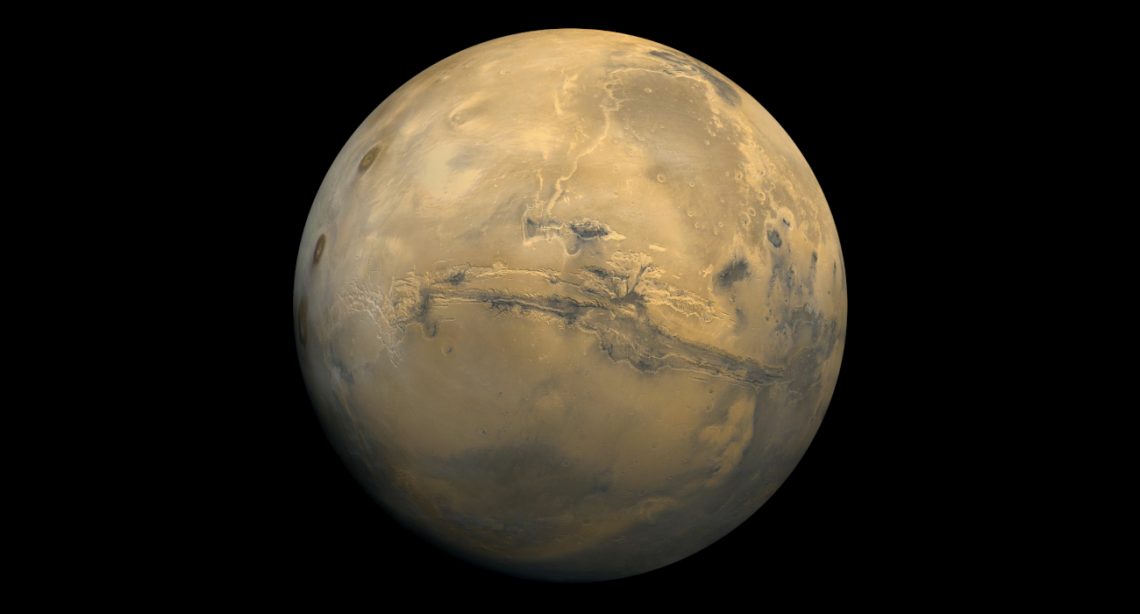

Orbiting the sun at an average of 229,000,000 km, the Red Planet is on average 79.4 million km farther from the sun than the Earth’s 149.6 million km orbit. To further complicate things, Mars bears an eccentric orbit around the sun, the most lopsided orbit out of the planets in our solar system. This adds up to a target that swings wildly in comparison to the Earth, making for launch windows that come about only once every 2.16 years (two years and 2 months).

The subject of launch windows is an interesting one but diverges somewhat from the topic at hand. To learn more about launch windows and how they are calculated, check out NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s aptly named article, Calculating Launch Windows.

Back to the topic of getting to Mars, we know that the launch window offers only a brief period in which a timely trip to Mars is possible. Even taking advantage of the two planets’ converging orbits, the trip takes around seven months given our current propulsion technology; a full month longer than the average astronaut’s tour on the International Space Station. Looking forward, propulsion systems such as SpaceX’s Super Heavy rocket aim to cut down the transit time to 80-150 days; a drastic reduction that still poses some challenges.

Operating in Low Earth Orbit, the ISS remains at an operating altitude between 330 and 435 km. Here, the station crew are afforded protection from harmful radiation by resting comfortably within the Earth’s magnetic field. Unlike the astronauts on the ISS, the pioneers that will set out for Mars will be leaving behind the protection offered by the Earth’s magnetosphere. As they strike out into the interplanetary medium they will encounter levels of radiation many times greater than their Earth-bound peers. In this empty region of space, no shelter is offered from solar wind and the radiation contained within.

…the 1200 millisieverts that a Mars mission astronaut would experience is as much as 120 abdominal/pelvic CT scans.

On any mission into space, radiation exposure is a major factor in astronaut safety. A trip to Mars is no exception with radiation exposure for a hypothetical three-year round-trip mission expected to be in the range of 1200 millisieverts. To make a comparison, the 1200 millisieverts that a Mars mission astronaut would experience is as much as 120 abdominal/pelvic CT scans. The career limit exposure for a NASA astronaut is up to 4000 millisieverts (or less, depending on age, body weight). Astronauts on the ISS expect to receive only 160 millisieverts per 6 month mission, substantially less than the Mars mission crew would experience over an equivalent amount of time.

Blazing the trail to Mars will be incredibly difficult and fraught with danger. Even once we account for the risks of leaving Earth’s protection there remains a multitude of challenges waiting at Mars. In the next segment, we’ll look at some of the difficulties that astronauts will experience once they make it into Mars orbit and attempt to make planet-fall on the Red Planet’s unforgiving surface.